Supreme Court Upholds VA Court Ruling Denying Veterans’ Benefits

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against two veterans who argued that their disability claims were unjustly denied, despite the evidence in their cases being evenly weighted.

In a 7-2 decision, the court determined that the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims is not obligated to review the Department of Veterans Affairs' application of the "benefit-of-the-doubt" rule in most instances. This rule mandates that the VA approve a veteran’s claim when the supporting and opposing evidence are nearly equal, as reported by Military.com.

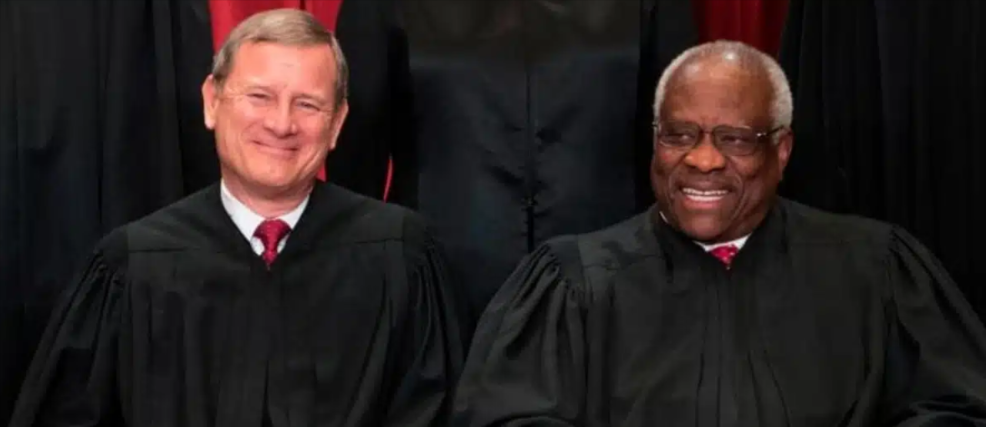

Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the majority, explained that the VA claims court, along with the Federal Circuit Court that upheld its ruling, was not legally bound to conduct a benefit-of-the-doubt review in these particular cases.

Instead, in his March 5 opinion, Thomas asserted that the claims court’s duty was limited to evaluating whether claims adjudicators or the Board of Veterans Appeals committed any errors, the outlet noted.

“We hold that the Veterans Court must review the VA’s application of the rule the same way it would any other determination — by reviewing legal issues [from the beginning] and factual issues for clear error,” Thomas wrote.

The case, Bufkin v. Collins, involved two veterans challenging their claims' denials. Joshua Bufkin, who served in the Air Force from 2005 to 2006, filed for disability benefits related to post-traumatic stress disorder about seven years after leaving the military. During his service, he struggled with training as a military policeman, citing marital stress as a contributing factor. Court records indicate that Bufkin claimed his wife had threatened suicide if he remained in the military, leading him to request a hardship discharge.

When Bufkin later sought VA healthcare and benefits, he argued that his condition was service-connected. However, disagreements among VA medical professionals regarding both his PTSD diagnosis and its connection to his service led to the rejection of his claim.

Norman Thornton, a former Army soldier who served from 1988 to 1991 and was deployed during the 1990-1991 Persian Gulf War, initially received a 10% disability rating for PTSD, which was later increased to 50%. Thornton appealed, asserting that his rating should have been higher.

In both cases, the Veterans Board of Appeals examined the evidence—concluding that Bufkin’s evidence was inconsistent and that Thornton’s case did not justify an increased disability rating.

The Veterans Court of Appeals later ruled that the claims adjudicators and the board had not committed errors, though it did not conduct a benefit-of-the-doubt review. On appeal, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals concurred that such a review was unnecessary.

When petitioning the Supreme Court, the plaintiffs contended that the law explicitly requires veterans to receive the benefit of the doubt. However, Thomas concluded that they did not present a valid legal argument, emphasizing that the veterans court can only overturn decisions when a clear error is present.

“After closely examining the way in which the VA conducts the approximate balance inquiry [of benefit-of-the-doubt evidence], we conclude it is a predominantly factual question and thus subject to clear-error review,” Thomas wrote.

Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Neil Gorsuch dissented, Military.com reported. Jackson, in her dissenting opinion, argued that veterans are entitled to have "any reasonable doubt on a material issue" resolved in their favor, as Congress originally intended.

“The court today concludes that Congress meant nothing when it inserted [into law,] in response to concerns that the Veterans Court was improperly rubberstamping the VA’s benefit-of-the-doubt determinations and also that the Veterans Court is not obliged to do anything more than defer to those agency decisions,” Brown wrote. “I respectfully dissent.”

In essence, the justices reviewed the case to determine whether the Veterans Court must examine the VA’s application of the benefit-of-the-doubt rule beyond merely checking for errors. The majority ruled that, in most cases, it is not required to do so.